I am uncommonly pleased to announce that a contract for the preparation of a publication has been cordially agreed between Amberley Publishing of Stroud and myself.

The book, currently titled The Archaeology of Postholes: Reconstructing Prehistoric Buildings, will have 60,000 words, with 130 illustrations, and while advance order lines will be waiting to take your call, I’d give it a couple of weeks, as I haven’t written it yet.

Many thanks to Miles Russell for his good offices.

This is the basic synopsis for the book which I developed last February. It will cover many of the topics covered so far on Theoretical Structural Archaeology, but with a linear rather than episodic narrative structure, and it will require a new set of black and white illustrations.

Many thanks to Miles Russell for his good offices.

This is the basic synopsis for the book which I developed last February. It will cover many of the topics covered so far on Theoretical Structural Archaeology, but with a linear rather than episodic narrative structure, and it will require a new set of black and white illustrations.

Synopsis: The Archaeology of Postholes: Reconstructing Prehistoric Buildings

The narrative of the book concerns how archaeologists understand postholes, which, on many sites, constitute the majority of the features found, although most will remain uninterpreted. Its central hypothesis is that postholes are the foundations of structures, which can only be understood by modelling the lost three-dimensional superstructure that their posts once supported.

The narrative of the book concerns how archaeologists understand postholes, which, on many sites, constitute the majority of the features found, although most will remain uninterpreted. Its central hypothesis is that postholes are the foundations of structures, which can only be understood by modelling the lost three-dimensional superstructure that their posts once supported.

The initial chapter considers the central importance of architecture to culture and archaeology. It introduces the reader to the evidence, and reviews current methodologies and assumptions. It then considers further how we should look for buildings, particularly, what we are looking for, and the role irregularity plays in our perception.

The third chapter deals with the principles of modelling structures from postholes, including the nature of timber, basic engineering and frame technology. The methodology outlined is based on the use of theoretical models, each demonstrated as a set of architectural drawings [Theoretical Structural Archaeology]. These principles are then applied in a series of case studies covering the main forms of prehistoric buildings and structures, producing additional evidence and new interpretations. The studies are chosen to give the narrative a technical and chronological shape. They introduce Interlace Theory, which is used to explain the position of posts in structures with a curving roof, such as class Ei buildings [aka ‘timber circles’].

The third chapter deals with the principles of modelling structures from postholes, including the nature of timber, basic engineering and frame technology. The methodology outlined is based on the use of theoretical models, each demonstrated as a set of architectural drawings [Theoretical Structural Archaeology]. These principles are then applied in a series of case studies covering the main forms of prehistoric buildings and structures, producing additional evidence and new interpretations. The studies are chosen to give the narrative a technical and chronological shape. They introduce Interlace Theory, which is used to explain the position of posts in structures with a curving roof, such as class Ei buildings [aka ‘timber circles’].

The overwhelming conclusion drawn from an analysis of the evidence is that prehistoric timber architecture and building was highly competent and technically accomplished, and capable of producing complex built environments reflecting the economic, cultural, and strategic needs of local populations and individuals.

Chapter Summary

Chapter 1. Why we know what we think we know

Set against the wider significance of architecture to the visual culture of the past, this chapter introduces the archaeological evidence for timber structures in British prehistory, and what we conventionally do with it.

Set against the wider significance of architecture to the visual culture of the past, this chapter introduces the archaeological evidence for timber structures in British prehistory, and what we conventionally do with it.

It starts with brief description of the author’s motivations for writing the book; these revolve around the difficulties experienced while working as a professional archaeologist trying to interpret a type of archaeology site that has been called ‘posthole palimpsest’. This type of site may have hundreds, even thousands, of unexplained postholes, and other features, so like all good investigations, it starts with something unexplained.

The aim of the book is to take the reader, by degrees, and with careful explanation, into a lost world of timber architecture.

The main narrative starts with a discussion of the central importance of architecture and the built environment, both to culture, and our perceptions of it, in terms of archaeology and the visual culture of the past. The view of architecture as a product of the environment, raw materials, and culture, with a regional basis and degree of continuity, is introduced. Another important thread is the notion of planned built environments, viewing them as the infrastructure of culture.

The power and influence of visual images in our understanding, despite the lack of evidence, is also considered. The subject of pyramids is then considered as an example of visual shorthand, engineering, architecture, and culture. This leads on a discussion of how the survival of stone monuments, and archaeological visibility in general, distorts our perception of both architecture and ‘civilisation’.

Pompeii, Akroteri, and, in particular, Biscupin, are used to illustrate the significance of chance survivals and preservation of ancient built environment. This includes a discussion of the agencies of wood preservation and destruction, which reinforces the relationship between architecture and environment.

Pompeii, Akroteri, and, in particular, Biscupin, are used to illustrate the significance of chance survivals and preservation of ancient built environment. This includes a discussion of the agencies of wood preservation and destruction, which reinforces the relationship between architecture and environment.

The next section deals with the archaeological evidence, how it’s handled and understood. It describes the excavation, recording, planning and publication of postholes and similar features from first principles. The comparative methods used to identify buildings and structures are discussed and deconstructed. It is argued that emphasis on shape, rather than structure, has given rise to simplistic models, spurious ethnography, and dysfunctional reconstructions. Further, a focus on the psychological, rather than technical motivations as an explanation for archaeology, has tended to result in the characterisation of the past as ‘other’.

Chapter 2. Looking for structure.

This chapter returns to the topic of how to look at, and understand, archaeological site plans. In short, how do we identify buildings and structures we have not previously seen, and without reference to known structures.

The first part of the chapter considerers building geometry as conventionally understood and contrasts this with the apparent irregularity in archaeological plans. It also returns to the issue of archaeological invisibility, perishable materials, and the use of posts as foundations. An important aspect of this section is scale, in terms of both buildings and wider built environments, as it applies to domestic, agricultural, military, and religious examples. It concludes with a discussion of the central importance of architecture to culture.

The next section deals with builders and architects, arguing that built environments require specialist skills, and that these are best preserved and transmitted by heredity or apprenticeship, on a model similar to the medieval system [masons].

The implications of this are that archaeological buildings' plans are artefacts, produced by a specialist group in society, much in the same way smiths produce metalwork, only buildings are more valuable and significant. Theoretical structural archaeology is therefore the study of this group of craftsmen and their technological culture.

One matter arising, dealt with at this point, is the issue of metrics and measuring systems, which may, or may not, be apparent in building and other plans. The final section deals with the issue of irregularity, and ‘systematic irregularity’. It can be readily observed that, apart from certain religious structures, nothing in the later prehistoric landscape was square. Looked at in detail, posthole structures are irregular and never square, much like the art and decoration of the period.

This phenomenon, dubbed ‘Systematic Irregularity’, is explored for the rest of the chapter, thus returning to the issues of symmetry versus irregularity in the hunt for structure, which began the chapter.

Chapter 3. Theoretical structural archaeology

This introduces the reader to the technological basis of timber buildings from first principles, starting with trees.

Buildings, like most of the prehistoric world, were made from timber, and wood was the principal fuel that heated them, so the first part deals with the growing of trees and the management of woodland. It examines the characteristics of principal native species as a building material. With the help of growth tables for oak, the relationship between posthole diameter and tree age/height is considered, as well as the structural implications of tapering timber.

Having considered the properties of timber as a building material, the text moves on with a consideration of posts and postholes as foundations. It explores how they work, considering issues such as depth, subsidence, and basic soil mechanics. The effects of wind, rain, ice and snow are discussed in relation to rigidity, and dynamic and static loading.

Having considered the properties of timber as a building material, the text moves on with a consideration of posts and postholes as foundations. It explores how they work, considering issues such as depth, subsidence, and basic soil mechanics. The effects of wind, rain, ice and snow are discussed in relation to rigidity, and dynamic and static loading.

The next section looks at the basics of timber buildings and roof design. It discusses the principle components, and the development of the roof truss with reference to medieval timber buildings.

At this point, four issues central to the analysis of archaeological plans are discussed:

1. The importance of reversed assembly;

2. The positioning of ties;

3. The limits imposed by timber;

4. The significance of simplified and offset jointing.

This is followed by a brief discussion about modelling buildings from archaeological plans using these insights, and the importance of geometry in making models ‘work’. The text examines the relationship between ground plan and roof shape with reference to the Neolithic ridge-piece roof, and suggests that the search for buildings can be viewed as a search for roofs.

Chapters 4-8. Case studies

From this point in the narrative onwards, the principles outlined in the previous chapter are applied to real archaeological plans in a series of case studies. These are aimed at solving some of the problems outlined earlier; by being able to accurately define and demonstrate the structural relationships between features, we gaining a better understanding of what we are looking for. Each illustrates a particular aspect of the correlation between archaeological plans and interpretive models, returning to the themes of explaining irregularity and recognising structure.

The studies are structured chronologically, following some of the principal developments in building architecture from the Neolithic onwards. Each has a brief introduction to the background archaeology. They illuminate not just the architecture, and therefore culture, of the period, but also continue to explore and expand the underlying themes of disentangling and interpreting site plans.

Chapter 4. Farmhouses made from trees

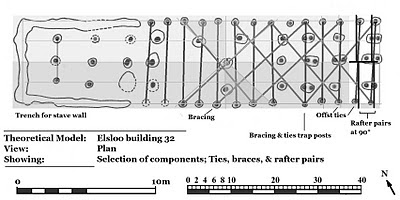

In the first of a series of case studies, the Neolithic longhouse is looked at in detail, using Northern European examples from Elsloo [Netherlands], and Olzanica [Poland].

The text continues to explore the nature of the ridgepole roof, in particular the positioning of ties in relation to the rafters as an explanation of the apparent irregular geometry of longhouse plans. This returns the argument to the subject of ‘offset’, already an important idea in the positioning of important structural joints, and hence the posts that supported them. The relationship between long tapering timbers and the layout and size of postholes in the ground plan is also considered. Another important observation is the probable position of braces, which together with the ties, ‘trap’ the internal posts.

Using the plan of Olszanica B1 the adaptation of building to draught animals and vehicles is discussed, as well the positioning of stairs in longhouses.

Chapter 5. Interlace theory and the architecture of power

Chapter five introduces an entirely new way of viewing the construction of curving roofs, named Interlace Theory, which, importantly, explains the disposition of posts in Class Ei buildings, erroneously known as timber circles.

Chapter five introduces an entirely new way of viewing the construction of curving roofs, named Interlace Theory, which, importantly, explains the disposition of posts in Class Ei buildings, erroneously known as timber circles.

Using Woodhenge as an example, it explains that the posts in a ‘post ring’ would not be simply joined one:one, but would be built up around a series of interlocking polygons. The multiple connecting elements of a post ring also connect between post rings, interlocking them to create a complex, but ridged, polygonal annular roof structure. These buildings have a distinctive pattern of ties and braces, which, as in longhouses, trap the internal posts.

These buildings vary in form, particularly in the probable treatment of the central area, but as a solution for roofing wide spaces, they persist into the Iron Age, and late examples from Navan Fort, and an unrecognised building from Gussage All Saints form part of the discussion. Interlace theory has significant implications for the understanding of architecture of large roofed structures.

Chapter 6. Round or polygonal roofs

This chapter deals with modelling roundhouses, starting with a review of archaeological evidence and existing preconceptions.

The idea of ‘Axial Symmetry’ is examined, along with other geometric properties of ground plans, as this is related to identifying and analysing roundhouse plans. A restatement of the basics of conical roofs and cone geometry leads to a case study of foundation loading for a range of roundhouses, which reinforces the idea of building as a traditional and dynamic craft. The issue of ‘drip gullies’ is examined, and it is concluded that in many cases these are wall foundation trenches marking a move to the polygonal load-bearing wall in the Middle and late Iron Age.

The idea of ‘Axial Symmetry’ is examined, along with other geometric properties of ground plans, as this is related to identifying and analysing roundhouse plans. A restatement of the basics of conical roofs and cone geometry leads to a case study of foundation loading for a range of roundhouses, which reinforces the idea of building as a traditional and dynamic craft. The issue of ‘drip gullies’ is examined, and it is concluded that in many cases these are wall foundation trenches marking a move to the polygonal load-bearing wall in the Middle and late Iron Age.

The chapter also looks at the implications of Interlace Theory for our understanding of ring beams, and the use of ties in these buildings. It reconsiders some of the classic roundhouse plans, including Pimperne Down, Cow Down, and Little Woodbury. Among the issues covered are the nature of entrances, stairs, floors, and other internal structures. This leads to a discussion of roundhouses as part of wider built environment.

Chapter 7. Built Environments

This chapter covers large-scale architectural structures, placing buildings within a built environment such as a farm or fort, and beyond this, the wider manmade infrastructure.

It looks at the relationship between architecture and such issues as water supply, drainage, and aspect. The requirement for a range of specialist buildings is considered. There is a discussion of small structures, often referred to by the number of posts, such as ‘four-post’ structure, in the context of the storage of food, fodder, and fuel.

The particular requirements of military structures such as palisades, ramparts, towers, and gateways are considered in relation to weapons and tactics. The case studies in this chapter revolve around the Late Bronze Age fort at Springfield Lyons and the fortified farmstead at Orsett Cock, both sites in Essex.

Chapter 8. Roman postholes

This chapter looks at some timber and earth structures built by the Roman army, with a case study of the postholes found on the berm in front of Hadrian’s Wall.

It considers the evidence from Caesar’s Gallic Wars and Trajan’s Column, and offers a new analysis of the posthole structures on the Antonine Wall. The postholes on the berm north of Hadrian's Wall are modelled as a temporary timber rampart, which together with the Turf Wall formed a temporary and defendable frontier, while the Wall was built.

The chapter also contains an account of the Vallum, suggesting it is an unfinished roadbed, which, like the Timber Wall, reinforces the idea of ‘dislocation’ and warfare during the period of the Wall's construction.

Chapter 9. Conclusions

The final chapter brings together the main threads of the narrative in two parts: how to interpret postholes and what they tell us about the prehistoric built environment.

It restates the principles of understanding the posthole evidence as foundations and in terms of their lost structural relationships. It stresses the importance of reversed assembly, ties, simplified jointing, interlace theory, and trees in explaining prehistoric building plans, particularly their apparent irregularity.

The central importance of architecture and the built environment to culture, and its significance as an expression of power, and therefore its importance to archaeology, is restated as central theme. The nature of architects and builders and their craft is considered as a mechanism of expression, development, and transmission of architecture in prehistory. How these ideas interact with the existing intellectual and visual preconceptions of the past is considered.

The book concludes that there is entire lost world of timber architecture hidden in plain view within our existing reports, and that what has been lacking is not the evidence for the built environment, but our ability, hitherto, to comprehend it.

So far so good; now all I have to do is write it. I'll make a start tomorrow......

16 comments:

Outstanding. Welcome to the world of published authors!

Thanks Gary, I am looking forward to outselling you, well, after I have written it and it's sold hundreds, obviously!

Congratulations!

Thanks Unknown, and Luckylibbet - I hope all is well in sunny California.

Congratulations; I can't wait to buy a copy!

All is definitely well in sunny California - but not a lot of 3rd century postholes around. Or at least not in my neighborhood. Just spent a week in New Mexico looking at pueblo architecture and tried to fit your philosophy around the generic National Park Service brochures - mind-bending! I think I will buy your book. Quite an entertaining archeological/building guy. Sorry, you fit into my weirder hobbies, and I'm probably not your normal fan.

Thanks Ornithophobe, - You & my mum!

Hi Lucklibet,

May have something relevant on the blog soon; I have been looking Native american architecture in Ohio with a colleague in the States. It is very interesting and very different from what happens in Europe; it is based on different principles and technologies, which developed from the different cultural and geographical conditions in the Americas.

Congratulations Geoff! I reckon it was those Archaeology cartoons that clinched it.

Seriously pleased for you mate.

Thanks Vincent, I will be sure tomention pyramids to ensure at least one sale Down Under!

Hi Geoff- You'll find Native American architecture in Ohio a very different proposition from that in New Mexico. Different environment = different building. But you know all about that. Mostly wet vs. dry I would expect. Interested to hear your conclusions though. - Heather

Hi Heather, you are so right, I have to be careful or I will have to check all of the Americas.

as you say, there is a wide range of environments, and different cultural requirements [-but No draft or domestic animals, and a different range of crops - for starters].

What I have seen, is that there is a very different technical approach [compared with Eurasia], and most of my fundamental assumptions about frame carpentry and assembly, did not apply in N America. Its is made more interesting, by European archaeologists using Native American 'parallels, to explain their own archaeological structures; big mistake.

Dear Geoff

Dear Geoff. I'm delighted by this. If you want any help with editing or proof-reading chapters I'd be happy to oblige.

best wishes

Ned

Thanks Ned - most kind - as you know I am in serious need of a good editing - I'll let you know if I actually secede in writing a chapter!

Hurray! This makes me happy!

Hi Martha, Great to hear from you, thank you so much.

Post a Comment