When you start

an excavation, or make an original observation, it may become your

responsibility to give things a name, which is not as easy as it might

seem.

When you start

an excavation, or make an original observation, it may become your

responsibility to give things a name, which is not as easy as it might

seem.

I inherited

an archaeological site named Orsett “Cock”, the Cock in Question was the local

pub, a perfectly reasonable and appropriate idea for archaeology in 1976, when google

was just a spelling mistake.

It was

working on the Orsett enclosure report, as I preferred to call it now, that I

had to start naming parts of theoretical model structures, although I also

floated an idea that I decided to call Systematic Irregularity.[1]

While it is

my understanding that this idea exists in other forms, as an archaeologist doing

detailed work on built environments, I had perceived that engineered structures

were never square or rectangular, an observation that applied to both to foundations of

small buildings and to layout of large ditched enclosures.

Systematic

irregularity is the deliberate avoidance of shapes comprising four right

angles, [i.e., having right angles in opposite corners], which is apparent in the

arts and crafts of Prehistory particularly the [Celtic] Iron Age.[3]

Previously discussed here.

Previously discussed here.

There is a

sort of self-evident truth about the general observation which only really becomes

significant when you consider its extent; this is something that goes much

deeper than curvilinear art and design.

- Enclosures and “Celtic fields”; [above: [4]] these are almost by definition not quite regular, often this may be perceived as product of topography, but when you consider the lowlands, where aerial photography has revealed thousands of examples the pattern is remarkably irregular, even if 2 right angles, or 2 sets of parallel sides [parallelogram / rhombus] occur, squares are exceptional.

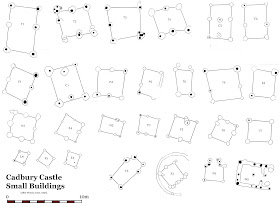

- Built environments; [above: [5]] While the majority of British Iron buildings are considered to be round,

smaller structures like 4 post structures [granaries] are always slightly

irregular with one posthole slightly out of position.

- Celtic art and design; one of the defining characteristic of “Celtic” and other Prehistoric material is the general lack of right angles and the reliance of arcs or curve; this curvilinear approach seems apparent in most aspects of material culture where evidence is available.

- Square structures; I am aware three types of exceptions;

- Roman-Celtic temples [above: [6]]

- Burial enclosures [below: [7]]

- Burial pits

Heathrow Romano-Celtic Temple with Grid [outer c. 35" x 32" - inner 17" x 14"] [8]

Systematic

irregularity appears far more extensive than might be expected from handmade variation, carelessness, or an artistic approach material that embraces the

curve; building and engineering in wood is about straight lines and regularity,

even in a circular structure.

Even though these

observations are made on the basis of a limited sample, they appear to be

generally true enough to advance a theory that systematic irregularity

represents a taboo against shapes with opposed right angles except perhaps for

the resting places of the dead and structures associated with Gods.

In terms of

observation, we are looking for the absence of something, which is only

possible when we are clear about what it is that is not there.

Also, we tend

only to notice things when they change, we are aware of the noise when it

stops, or an object when it is missing, so it is only in contrast with the

Roman culture for example, that we become aware that something is different.

It is not

just the forts, buildings and art that change but utilitarian objects like

swords and shields no longer have curving edges, whatever belief system drove

systematic irregularity it was not generally shared by the Romans.

Coincidentally, it is the Roman fort at Vindolanda that provides an intriguing strand of evidence; when the fort is rebuilt in the Severan Period [per. VI] there is an annex with rows of stone roundhouse foundations.[9] I would interpret these as being built to house hostages from those tribes in the intervening or adjacent areas between Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine frontier held to ensure their cooperation, [ as suggested by Tony Birley [9]]. What is important about these buildings is that they imply that intended occupants, presumable British, won’t live in the rectangular structures normally built by the Romans.

Coincidentally, it is the Roman fort at Vindolanda that provides an intriguing strand of evidence; when the fort is rebuilt in the Severan Period [per. VI] there is an annex with rows of stone roundhouse foundations.[9] I would interpret these as being built to house hostages from those tribes in the intervening or adjacent areas between Hadrian's Wall and the Antonine frontier held to ensure their cooperation, [ as suggested by Tony Birley [9]]. What is important about these buildings is that they imply that intended occupants, presumable British, won’t live in the rectangular structures normally built by the Romans.

It is difficult

to make this argument for individual types of articles, for example, there can are

good practical reason why a sword should a curved edge, as well as technical

reasons evident in the earlier cast bronze swords from which they developed. So, in many ways, the strength of the argument

lies in the irregularity buildings and larger engineered structures like

enclosures.

Regular Irregularity

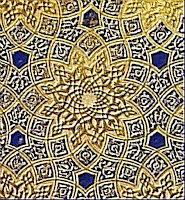

It is worth

considering irregularity in structures more generally, although a good example is

Moslem art & architecture which is also systemically irregular or rather

systematically imperfect, while it may only be perceptible to the craftsman,

geometric perfection is deliberately avoided, although never to the point where

the art or structure is compromised, [left [10]]. As an archaeologist I am always wary of

assuming that ideas originate with the culture well known for expressing or

documenting them; practices in architecture are the result of a much longer

term technical evolution. The earliest

buildings in Western Europe are the longhouses of the LBK Neolithic farmers which

have “irregular” looking plans apparently lacking the precision of later rectilinear

buildings, which is legitimate expectation. [11]

While this all

adds to impression of simplistic huts built by primitive people as illustrated in

the visual culture of the past, in reality it is the footprint a complex

building technology which can only be understood in 3 dimensions.

Although they

do not conform up to our expectations of regularity, it has been my experience

that the layout of prehistoric building is very precise in terms of the

projected superstructure. More

concisely, it is my understanding that because these structures have reversed

assembly with offset jointing, the apparent irregularity in the foundation is

contrived to create perfectly aligned rafter pairs to form a symmetrical roof.

So here, at the

beginning of timber architecture in Western Europe, we have a structural system

where what we might perceive as irregularity, is an integral part of a system

designed to create regular symmetrical structure.

There are

seemingly good reasons why opposing right angles might not be present in this type

of structure period, but there also an interesting tendency towards slightly

tapering buildings which is also reflected in long barrows tombs, [houses for

the dead].[12] It could be argued that during this period circularity was reserved

for ceremonial or religious structures.

The Mundane Circle

There is a

radical change to a preference for circular structures for the living and the

dead in the Early Bronze Age, which I associate with the arrival of the Beaker

Cultural Group.

This remains

the general pattern into the Late Iron Age, where It could be argued that

squares were reserved for ceremonial or religious structures during this

period. This apparent emphasis on

circularity in domestic buildings makes systematic irregularity difficult to

detect except in those small utilitarian buildings that are recognised. The

technical issues of creating circular buildings from straight timbers, especially

large ones, is easily overlooked; compared to rectilinear systems, they are more

complex, require more resources, are less flexible, and more difficult to

combine. In terms of circularity, it is also important to understand that many structures are effectively polygonal being constructed with straight horizontal timbers.

This remains

the general pattern into the Late Iron Age, where It could be argued that

squares were reserved for ceremonial or religious structures during this

period. This apparent emphasis on

circularity in domestic buildings makes systematic irregularity difficult to

detect except in those small utilitarian buildings that are recognised. The

technical issues of creating circular buildings from straight timbers, especially

large ones, is easily overlooked; compared to rectilinear systems, they are more

complex, require more resources, are less flexible, and more difficult to

combine. In terms of circularity, it is also important to understand that many structures are effectively polygonal being constructed with straight horizontal timbers.

The notion of

sacred geometry is just a cliché of the mysterious; however, there is a very

real and specialised understanding that is required to create architecture. In

many ways, it is this knowledge of practical geometry that defines architects/engineers

as distinct class in society in much the same way as we might perceive smiths,

only much older and more fundamental. Ultimately,

it is the culture of these craftsmen that theoretical structural archaeology is

attempting to understand.

The pattern

of mixed agriculture upon which our prehistoric and historic culture was based

was only possible through effective architecture and civil engineering. Regardless of how collective or specialised

we might wish to view the process of construction, there has to be a mind with

the appropriate set of conceptual skills in control of it all. The built environment is so ever present that,

except when it goes wrong, we hardly question how it got there or consider who

designed it. Much the same lack of

curiosity is evident in archaeology where the evidence for structures is ever

present on some types of site in the form of postholes which are largely

ignored to such that the concept of a built environment is not even discussed;

all the processes that happen indoors, especially those requiring specialist

buildings are not part of our understanding of the past.

Profane Geometry

Profane Geometry

Profane Geometry

Profane Geometry

Our awareness

of the use of geometry in prehistory, like culture in general, has become

fixated on the scared, the ritual, and what that tells us of peoples’

conception of themselves, although in reality, geometry is rarely considered beyond

the superficially of shapes, usually circles, which magically infers a

connection between things regardless of context or scale.

Systematic irregularity

does not have to be explained, since this would require detailed knowledge about

the thinking of a preliterate culture.

It is a useful observation, especially to the process of theoretical modelling

of buildings which is based on creation of geometrically accurate structures. It also has to be taken into account in the

process of identifying new posthole structures, which also has a prejudice

towards regularity of pattern as evidence of structural relationships.

Sources and

further reading:

[1] G. A. Carter, 1998:

Excavations at the Orsett ‘Cock’ enclosure, Essex, 1976. East Anglian

Archaeology Report No 86.

Previously discussed here:

http://structuralarchaeology.blogspot.co.uk/2009/03/24-systematic-irregularity-why-almost.html

[2] G. Bersu, 1940:

Excavations at Little Woodbury, Wiltshire. Part 1, the settlement revealed by

excavation. Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society, 6, 30 -111

[3] I am using the term “Celtic”

in a fairly loose and generic, not wishing to get into issues about the use of

the word in archaeology, notwithstanding I have no particular view on the distribution of systematic irregularity.

[4] Illustration cobbled

together from Interpretative Devolution and the Iron Ages in Britain, B. Bevan,

ed. Fig 10.3, p153 [Scrooby Top]. B. Cunliffe, 1978: Iron Age Communities in

Britain: An Account of England, Scotland and Wales from the Seventh Century BC

Until the Roman Conquest. 2nd edition. Routlage & Kegan Paul. Figs: [11.6]

Aldwinkle Northhamptonshire, [11.5] Casterley Camp, Wiltshire, [11.14]

Portsdown Hill, Hampshire, [2.4] South Lodge, Dorsett

[5] Taken from: Downs, Jane,

1997: The Shrine at Cadbury Castle: Belief enshrined. In Adam Gwilt and Colin

Haselgrove, eds: Reconstructing Iron Age Societies. Oxbow Monograph 71, Oxford,

145–152

[6] A. C. King & G.

Soffe, 1994: The Iron Age and Roman temple on Hayling Island, in A. P.

Fitzpatrick and E. L. Morris, eds.: The Iron Age in Wessex: recent work,

Salisbury: Trust for Wessex Archaeology, 114-16

[7] S. Piggott, 1965: Ancient

Europe, Edinburgh University Press: Fig 131, p 233

[8] W. F. Grimes and J.

Close-Brooks, 1993: Caesar’s Camp, Heathrow, Middlesex. Proc Prehist Soc 59,

299-317

[9] Burley R 2009, Vindolanda A Roman fort on

Hadrians Wall. Amberley ISBN978-1-84868-210-8 p. 140

[10]

[15] From Figure 5: http://www.geometricdesign.co.uk/perfect.htm Taken

from: Martin Lings, 1987: Splendours of Qur'an Calligraphy and Illumination

ISBN: 0500976481 Interlink Pub Group Inc.

[11] PJR Modderman

(1970), 'Linearbandkeramik aus Elsloo und Stein 2.' Tafelband, Leiden Univ.,

Faculty of Archaeology.

PJR Modderman (1975), 'Elsloo, a

Neolithic farming community in the Netherlands,' in Bruce-Mitford,

R L S, Recent archaeological excavations in Europe, Chapter IX.

PJR Modderman (1985), D'ie Bandkeramik

im Graetheidegebiet, Niederländisch-Limburg.' Berichte der Römisch-

Germanischen Kommission, 66::25-121.

"There is a radical change to a preference for circular structures for the living and the dead in the Early Bronze Age, which I associate with the arrival of the Beaker Cultural Group."

ReplyDeleteDid you catch the latest on these blokes?

http://biorxiv.org/content/biorxiv/early/2017/05/09/135962.full.pdf

"Beginning with the Beaker period, and continuing through the Bronze Age, all British individuals harboured high proportions of Steppe ancestry and were genetically closely related to Beaker-associated individuals from the Lower Rhine area. We use these observations to show that the spread of the Beaker Complex to Britain was mediated by migration from the continent that replaced >90% of Britain’s Neolithic gene pool within a few hundred years, continuing the process that brought Steppe ancestry into central and northern Europe 400 years earlier."

They brought their own foreign yDNA (male), various flavours of R1b-M269.

For instance, the 'Amesbury Archer's' relative/"companion" is R1b1a1a2a1a2c a.k.a. yDNA R1b-L21.

Same as me. And a hefty majority of Isles men, right down to the present day.

This isn't "culture complex". It's not even a "Folk". It's a hugely powerful (or very lucky) clan. From Germany and the Low countries. And they rolled right over the local farmers and pretty much annihilated the men, at least, by fair means or foul. Did it in a lot of France and Italy and later, Iberia as well.

These were definitely Chaps Who Got Things Done. With a subject populace for labour, at least to begin with, before they gave them the plague/bred them out/killed them off. Even the Anglosaxons etc. didn't make even a fraction of the genetic impact.

Thanks DB,

ReplyDeleteThat is is very interesting, and much as I have always suspected; I can seen things in the architecture which reflect these processes.

Much as I hate to go there, I suspect there is a connection to tented culture in the preference for domestic circularity.

These chaps had better bows and arrows which counts for a lot.

Which one of those genes is Blue Blood?

.. . . and Iberia is the key; it's an early centre of metallurgy - the hub of trade and maritime technology, the point of contact with the Mediterranean etc etc, people from the Steppe don't bring that with them.

ReplyDelete"Which one of those genes is Blue Blood?"

ReplyDeleteWell the unlucky Tsar Nicholas II was R1b, and therefore any other princes and kings of the House of Oldenburg.

As was Henri IV (Bourbon), R1b1b2a1a1b

It's claimed that most of the Windsors (Saxe-Coburg-etc. etc.)down to George VI are, (House of Wettin).

Albert II of Belgium. Tsar Simeon Borisov of Bulgaria, and so on. Seems to be rampant among European aristocracy, which isn't all that amazing as most of Western Europe is saturated with the stuff, even scum like me.

There's been a load of new ancient DNA stuff put out in the last week or so, and people are still thrashing around in the deluge of data. I'm staying well back as resolving all it is likely to be a fairly messy and ill-tempered process, generating much schadenfreude. There's a more than a few vested interests and lengthy careers at stake here, particularly among the Immobilist faction of prehistorians.

"Cultural packages" did arrive. Along with very large numbers of the people who used it, lock, stock and campaniform pot. They brought their wives, children, probably language, architecture, military technology and so on. And they kept on arriving. Everybody else either knuckled under, died, or ran away.

We are here, and they are gone.